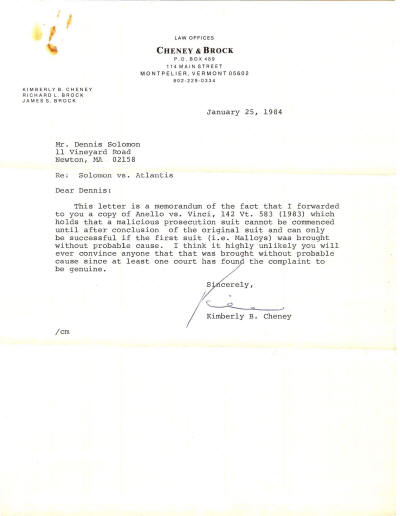

During the Fall of 1975, Malloy & Mordecai criminally schemed to defraud the other shareholders of Atlantis Weathergear by retiring the compnay's revolving bank credit to precipate a cash flow crisis and then presenting false and misleading financial statements during a January, 1976 stockholders meeting, to force a 'sale of the assets' - never perfected as the vote they forced was without mandatory notice under State and corporate by-laws. After an investigation, the shareholders retained former Vermont Attorney General Kimberly Cheney, and filed suit against Malloy and Mordecai.

Malloy countersued alleging that Solomon, who was in Washington, D.C., had called a Washington Post reporter, Dan Morgan, regarding an article Morgan had written on the "Great Potato Scandal of 1976" and slandered Malloy by truthfully recalling the conversation aboard the yacht of Stephen Green, the EF Hutton potato futures specialist, regarding how "they (Greene & Malloy) made money both ways - as the price rose and then as it fell". Solomon asked Morgan if Malloy was involved.

Prior to the 1980 Atlantis Trial, the CFTC (Commondities Futures Trading Commission) conducted a thorough investigation into the "biggest default in 104 years", naming Jack Simplot, Peter Taggeres, Pressner Trading Company and Stephen Sundheimer as perpetrators.

During the Atlantis trial, Malloy would reluctantly testify on the stand that he "was asked to leave E.F. Hutton in March of 75". At first, Malloy claimed that he didn't "know the people involved." When, under further examination, Malloy was presented with copies of his potato futures trades , he testified that he "did trade with them (Pressner and Sundheimer)" during the period that the CFTC found the 'manipulation' was in play. (see below)

Stanley Levin, a member of the MERC, testified that Sundheimer told his associates that the "shorts" planned to default (see below).

Judge Gibson personally heard the full testimony; the relationship between Malloy and Sundheimer, the move of Malloy's potato trading from EF Hutton to Pressner, and the indictment of Pressner and Sundheimer. Gibson heard that Malloy could not present any of Solomon's statements which were untrue, nor any means by which Solomon's private call to Morgan caused 'brokers on the floor of the exchange snickered" at him (Malloy).

Nonetheless, Gibson concluded that "Solomon had insufficient evidence to call a newspaper reporter". (see Conclusions of Law, 1981).

Gibson's ruling silenced any press inquiry of the Atlantis case, and unleashed Malloy and the Atlantis Cartel to wreck havoc with the Vermont Supreme Court and the Country. In 1986, the Vermont Supreme Court would pay the price as Gibson, Hill and Hayes were indicted for judicial misconduct.

The ruling remains standing however, a dangerous precedent in Vermont Law, a reminder of judicial corruption, and Gibson's Disgrace.

TIME MAGAZINE - June 7, 1976

"The Great Potato Bust"

Most Americans have never heard of Jack Richard Simplot. But

they know of his product and doubtless have eaten it. As the "Idaho

potato king," as well as the nation's largest supplier and processor of

potatoes, Simplot funnels millions of ready-cut spuds to McDonald's,

which turns them into millions of French fries to go with its quick-food

goodies. But Simplot has a reputation as a wheeler-dealer in his

favorite commodity, and last week he found himself entangled in the

biggest potato-futures default in the 104 years of the New York

Mercantile Exchange.

CFTC Hears Sworn Testimony on Stephen Sundheimer

and the Planned Default - Stanley Levin

STROBL v. NEW YORK

MERCANTILE EXCHANGE

NOS. 648, 781, DOCKETS 84-7328, 84-7770.

768 F.2d 22 (1985)

Joseph STROBL, Plaintiff-Appellee Cross-Appellant,

v.

NEW YORK MERCANTILE EXCHANGE, Clayton Brokerage Co. of St. Louis,

Inc.,Heinold Commodities, Inc., Thomson and McKinnon, Auchincloss,

Kohlmeyer, Inc., Ben Pressner, Pressner Trading

Corp., John Richard Simplot a/k/a Jack Richard Simplot, a/k/a

J.R. Simplot, J.R. Simplot Company, Simplot Industries, Inc., Simplot

Products Company, Inc., Peter J. Tagares a/k/a Peter J. Taggares, P.J.

Taggares Company, C.L. Otter, SimTag Farms, Kenneth Ramm, A & B Farms,

Inc., Hugh D. Glenn, Gearheart Farming, Inc., Ed McKay, Harvey Pollak,

Henry Pollak, Henry Pollak, Inc., Henry A. Pollak & Company, Inc.,

Robert Reardon a/k/a Bobby Reardon, F.J. Reardon, Inc., Alex Sinclair,

Sinclair & Company, Stephen Sundheimer,

Charles Edelstein, James Landry a/k/a Jim Landry and Jerry Rafferty,

jointly and severally, Defendants, John R. Simplot, J.R. Simplot Co.,

Simplot Industries, Inc., P.J. Taggares, P.J. Taggares

Company and SimTag Farms, Defendants-Appellants Cross Appellees.

United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.

Argued February 13, 1985.

Decided July 5, 1985.

MALLOY:

3 Mr. Johnson called me. I had been his

4 personal assistant, second in charge of E.F.

5 Hutton's Commodity Department until March of ‘75

6 at which time it was decided I would just trade

7 as a customer. I still maintained my own office

8 at E.F. Hutton, still went in most days when I was

9 in New York, and continued to trade through E.F.

10 Hutton.

Pages 274-275

22 but I have no involvement with the potato

scandal.

23 I traded potatoes during that period of time

24 just like I traded every other commodity during

25 that period or time but I don't know the people

1 involved, was not involved,

*************

Page 320-321

1 It is Stephen?

2 A. Stephen Sundheimer, yes, I am.

3 Q He is associated with a trading firm known as

4 Pressner Trading Company?

5 A. Yes, he is.

6 And you traded with Pressner Trading Company yourself

7 A. Yes, I have traded with them.

8 Q.

And specifically, you traded

with Pressner Trading

9 Company in March, April and May or 1976?

10 A. No.

11 Q. You didn’t. You traded --

12 A. I'm sorry, Mr. Cheney, can you give me the

13 months?

14 Q. March, April and May of 1976?

15 A.

That would have been after I left E.F.

23 Q. And Pressner Trading Company wag indicted in the

24 Simplot scandal, wasn’t it?

25 A. I don't know if their firm was. Mr. Sun-

2 Q. Sundheimer was

Trader Wins Potato Case

As a result of the potato-futures default in 1976, a Federal District Court jury in New York has awarded Joseph Strobl $460,000, which under antitrust law is tripled, to $1.38 million.

Mr. Strobl, now 67 years old, is a Detroit investor and former operator of amusement facilities. He will also get interest, according to his lawyer, Christopher Lovell, a partner in Lovell & Westlow, a New York law firm.

Defendants in the case were J. R. Simplot, the Idaho potato producer, and P. J. Taggares, a potato processor. They were accused of conspiring to manipulate the price of potato futures on the New York Mercantile Exchange. They sold many contracts through the spring of 1976, depressing the price, and then in May told the exchange they could not make delivery. It was one of the biggest defaults in the history of commodity trading.

Mr. Lovell said after the verdict Friday that his client held 116 potato contracts of 50,000 pounds each, which he had bought at about 17 cents a pound, and that he lost $462,500 in the default when all contracts were liquidated at 9 1/4 cents a pound.

GIBSON'S RULING - March, 1981

WASHINGTON SUPERIOR COURT

DOCKET N0. S23-771Wnc

DENNIS J. SOLOMON, DEAN W. MELEDONES,

PHILLIP SOLOMON, ROBERT ELDERIDGE,

WILLIAM D . MELEDONES and JULIUS GOODMAN, Plaintiffs

vs.

ATLANTIS S DEVELOPMENT, INC.,

PATRICK E. MALLOY, III,

MARK A. MORDECAI and ATLANTIS WEATHERGEAR, INC., Defendants

FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW (Order for Judgment 23 March 1981)

The above matter came on for hearing before the Washington Superior Court on February 19, 21, 22, 26, April 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, May 19, 20, 21 and 22, 1980.

The Plaintiffs were represented at the hearings by Kimberly B. Cheney, Esquire, and James S Brock, Esquire. The Defendants were represented by Robert D. Rachlin, Esquire,and Robert A. Mello, Esquire.

Upon consideration of the pleadings, the evidence, the representations of counsel, and the requests for findingsand memoranda of law, the Court makes the following; findings of fact:

…..

Finding of Facts related to Malloy’s counterclaim – Great Potato Scandal of 1976

-Page 46-

XI. DEFENDANTS' COUNTERCLAIM

220. A few months after the January 19, 1976 stockholders and directors, an article appeared in the Washington Post regarding a scandal in the potato futures market. An individual by the name of John R. Simplot had defaulted in his obligation to make delivery of potatoes under the futures.

-Page 47-

contracts, and this was the first time such a default had occurred in the commodity futures market. Simplot eventually was convicted in the Federal-Court of attempting unlawfully to influence the potato futures market. Malloy was not mentioned in the 'Washington Post article which reported the Simplot default.

221. Section 13 (b) of the Commodity Exchange Act, 7 U.S.C.A.§1, et seq., provides as follows:

"It shall be a felony punishable by a fine of not more than $100,000 or imprisonment for not more than five years, or both... for any person to manipulate or attest to manipulate the price of any commodity in interstate commerce..."

222. Solomon read the Washington Post article in May of 1976. After reading the article, Solomon called Daniel Morgan, head of the national desk for the Washington Post. Solomon suggested or implied to Morgan that Malloy had been participating in a manipulation of the potato market.

223. Solomon knew that Malloy traded in potato futures. While sailing in May 1975, during the discussions concerning, Malloy's investment in Atlantis, Solomon had participated in a conversation with Malloy and a Stephen Greene about the potato futures market. Solomon did not then have reason to believe that the conversation was about any illegal activities. At the present time, he is not sure about this, but his suspicions are purely speculative.

224. Defendant Patrick E. Malloy was known to the public through the news media as a significant trader in the commodity futures market, especially with respect to potato futures. Ma Malloy traded in potato futures through Stephen Sundheimer and Pressner Trading Corporation at the time of the default.

-Page 48-

225. Stephen Sundheimer was an individual whom the Commodity Futures Trading Commission also

investigated with respect to the default in the potato futures market.

226. Pressner Trading Corporation was a large corporation engaged in buying and selling for customers accounts potato futures contracts. It was also under investigation by the potato futures trading.

227. In his discussion with Morgan, Solomon gave Morgan Malloy's telephone number and the telephone number of Malloy's employer at E. F. Hutton. Morgan then telephoned Malloy several times.

228. Morgan started by asking Malloy general questions about potato futures and the potato futures market. When Morgan's questions started to become more personal and private, Malloy asked him why he was being asked these questions. Morgan then told Malloy that he had information that Malloy was participating in a manipulation of the potato market. When Malloy asked Morgan the source of his information, Morgan stated that it came from one Dennis Solomon. Malloy then explained to Morgan that Solomon was angry with Malloy over a business dispute. When Morgan learned that he stopped calling Malloy.

229. In addition to calling Malloy, Morgan also called Malloy's former supervisor, David T. Johnston, director and

-Page 49-

senior vice president at E. F. Hutton. Johnston held Malloy in "the highest esteem" from the time of his employment with that company throughout all the incidents referred to in the testimony. Malloy's reputation did suffer in the eyes of Mr. Johnston. (Defendants' Answer to Plaintiffs' Request for Admission of Fact.)

230. Solomon discussed this matter with "quite a few people" besides Morgan, one of whom was a Dr. Frank guest, director of a program sponsored by the Association of American Colleges in Washington, D.C.

231. Solomon never called, Malloy or Greene to seek clarification of-the May 1975 conversation he had

overheard.

232. For at least a week or so, brokers who worked on the floor of two different commodity exchanges came upto Malloy and either questioned him about the Simplot default or made kidding remarks about it.

233. Wall Street is a community where reputations for honesty are important. To those floorbrokers whom Malloy knew as a friend or as a business associate Malloy would explain the situation in response to the above comments.

234. There were some floorbrokers who made snide remarks to Malloy about rumors that they had heard about his alleged involvement with the Simplot default.

235. Solomon presented no evidence at the hearing that would prove or tend to prove that Mallow ever engaged in any wrong, unlawful or manipulative practices in connection with potato futures or the potato futures market.

-Page 50-

236. The telephone call from Morgan to Malloy and the questions and comments from other brokers caused Malloy some personal outrage and embarrassment for a period of time.

237. .There is no evidence that Malloy suffered any financial damages as a result of the actions of Dennis Solomon.

CONCLUSION OF LAW (Page 61-62)

13. Solomon, in making his unfounded telephone call to Morgan of the Washington Post, slandered Malloy in attempting to implicate him in the potato futures scandal. The conversation which Solomon overheard between Malloy and Greene more than one year before was insufficient basis on which to form an opinion about illegal trading on the part of Malloy-in potato futures and insufficient reason to call an investigative reporter. Had he been interested in learning the truth, Solomon could have called Greene or Malloy. The Court can only conclude that, by calling Morgan, Solomon meant to embarrass and harass Malloy and that his motive was malicious. Malloy did suffer embarrassment and temporary injury to his reputation. He claims no monetary loss, but seeks and is entitled to compensatory and punitive damages for embarrassment, personal outrage and temporary injury to his reputation. Lancour v. Herald and Globe Association, 112 Vt. 471 (1942). Defendant Malloy shall be awarded judgment on his counterclaim against Solomon in the amount of $2,500 compensatory damages and $2,500 punitive damages.